OneManGang

Senior Member

- Joined

- Sep 7, 2004

- Messages

- 1,851

- Likes

- 8,240

Tennessee vs The Maxims vs Florida

Elsewhere on this board there is a thread asking “Why do the Gators have our number?”

I've stated before but it bears repeating. Teams like Florida, Alabama and Georgia win big games because they believe they are going to win the given big game. The Vols are in that, “Gee, it would really be great to beat the Gators or Tide or Dawgs or whomever” category. Those teams come to the game with an attitude of, “We got this.”

The Vols used to have that swagger, that attitude, but no more. Hence winning big games used to be expected but now such victories are few and far between.

“But how,” you may ask, “do we get that back?”

There is only one way: The Vols have to develop confidence in themselves and go out there and actually win big games.

As we assess Saturday's tilt against the Gators we would do well to heed the words of the Ancient Philosopher: “The fight may not always go to the strongest, nor the race to the swiftest … but that's the way to bet.

And so it goes.

As the first half unfolded, your Fearless Scribe had a thought that Vol fans may, just may, have been getting a glimpse of what Tennessee could look like in a couple of years assuming the team continues to improve and really begins to learn HeadVol Heupel's system. That's a big assumption, but if true, the Vols could well be on the way to being one scary football team in a few years.

*********

Marine radio post on Guadalcanal, 2030 Hours, 14 October 1942

The Marines on Guadalcanal were understandably nervous about ships approaching during the night. The night of 14 October 1942 was no different. Just two nights before there had been a bloody naval melee within sight of the Marine positions that cost the US Navy two cruisers sunk and three more heavily damaged along with several destroyers and ultimately cost the Japanese the battleship Hiei. Two American Admirals, Dan Callahan and Norman Scott, had been killed and Japanese Admiral Abe had been seriously wounded.

Then just last night a pair of Admiral Mikawa's heavy cruisers had battered Henderson Field with over 1,000 rounds of 8-inch high explosive shells and even more lighter rounds from their secondary batteries. So when a voice came over the radio asking for information about the tactical situation off the coast, the radiomen refused to comply. Finally, another voice came on, “Tell your Big Boss that Ching Lee is here and I need the latest information.” Lee and the “Big Boss” on Guadalcanal, Marine Major General Archer Vandergrift, were old friends and the radiomen soon passed on the unhappy tidings that there really wasn't much intel other than what was already known.

A distant relative of Robert E. Lee hissownself, Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee (USNA 1908) was one of the Navy's leading experts on battleship tactics and, more importantly, had been a key figure in the development of the SG surface search radar and taught his troops how to get the most out of the new technology. His last name sounding vaguely oriental earned him the nickname “Ching” while at the Academy in those very un-PC days. A native of Kentucky, Lee was also a very proficient marksman and that talent earned him a spot on the 1920 US Olympic marksmanship team which won nine gold medals.

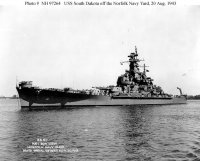

14 October 1942 found Lee commanding Task Force 64 consisting of the battleships USS Washington (BB56) and South Dakota (BB57) along with the destroyers Walke (DD416), Benham (DD397), Gwinn (DD433) and Preston (DD379).

TF64 was the hole card. After the loss of the carrier Hornet (CV8) at the Battle of Santa Cruz where the carrier Enterprise (CV6) was damaged and the losses on 13 October, Lee's little fleet was the only major strike force available. Should anything happen to the two battlewagons, Enterprise with her forward elevator jammed up, would be the only major fleet unit left to oppose Admiral Kondo's Advance Force and keep his dreadnoughts from blasting Henderson Field into oblivion and landing massive reinforcements to the Japanese land forces rendering the Marine position on Guadalcanal untenable. The South Pacific Force commander, Admiral Bill Halsey, was going all in.

At the main Japanese base at Rabaul in the early hours of 14 October, Admiral Kondo was readying his response to the loss of Hiei. He decided to make a run that night with a task force centered on the Hiei's sister ship Kirishima. The Japanese were going out loaded for bear. Besides Kirishima, Kondo's fleet boasted two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and nine destroyers. Following behind would be four transports carrying a regiment and tons of much-needed supplies for the soldiers of Dai Nippon on Guadalcanal.

To the casual observer it would seem the Japanese were seriously out-gunned in the battleship department, but one needs to remember that Kondo's ships outnumbered Lee's. None of the Japanese ships had surface-search radar but their crews had been trained in night combat and were quite proficient at it.

After nightfall, Lee's little fleet closed on Guadalcanal from the south west. By 2100 (9pm) he was passing by the northern tip of the island and made a turn to starboard to pass several miles north of Savo Island, a small volcanic island about 12 miles northwest of Cape Esperance, the northern tip of Guadalcanal. There were so many ships, Japanese, American and Australian, sunk in the waters around Savo that American Sailors referred to it as “Iron Bottom Sound.”

Kondo closed on Savo a few minutes later. He had split his force into three components: an outer screen of the light cruiser Sendai and three destroyers under Admiral Hashimoto, an inner screen with light cruiser Nagara and four destroyers under Admiral Kimura and finally the bombardment group commanded by Kondo himself in the heavy cruiser Takao, with Kirishima, the heavy cruiser Atago and two destroyers.

After another turn to starboard, Lee was passing east of Savo as Hashimoto was approaching from the northeast at 2200. Hashimoto, unaware of Lee's ships, split off two of his destroyers to sweep the area west of the island and see if he could find the Yankees a Japanese patrol plane had spotted that afternoon.

By 2300, Lee had turned due west toward Guadalcanal when the radar on Washington picked up Sendai about 9 miles distant. South Dakota soon had her and her escorts on radar as well and at 2317 both battlewagons opened fire.

Hashimoto must have thought a volcano had erupted as all fourteen 16-inchers opened up at him. Quickly Sendai and her two escorts turned hard back the way they had come, making smoke. He then turned back toward Savo. Meanwhile, the American battleships ceased fire as the destroyers in single file in front of them opened up on Hashimoto's detached pair coming around Savo from the northwest.

Following close behind Hashimoto's destroyers came Kimura's ships and behind him, Kondo's, all making flank speed. At this point the Japanese were on the east side of the strait while the Americans were headed on a reciprocal course on the Guadalcanal side. The American destroyers were in a column with Walke in the lead, then Benham, Gwinn and Preston. Preston was roughly 5,000 yards, or about three miles, ahead of the battleships.

By 2333, the American destroyers were exchanging fire with Kimura's ships when Murphy's Law came into effect.

South Dakota's electrical system had been bedeviled by sporadic failures due to damage inflicted at Santa Cruz. Now it picked this critical moment to completely fail. Out of control and blind as a bat, the battleship stumbled out of line TOWARD the Japanese.

Targeting the destroyers, Kimura's ships shot first, shot faster and shot more accurately. Preston died first under an avalanche of shells that wrecked her upper works and put huge holes in her hull. At 2336 she rolled over and sank taking 115 of her crew with her. The Japanese now sent a swarm of Long Lance torpedoes at the Americans. Six minutes later Walke, under a similar heavy fire took one of the “fish” which set off one of her forward magazines and blew the entire bow off. She sheared off to port and quickly went under. At 2338, another Long Lance found Benham and blew most of her bow off. She could still make about 5 knots and limped away to port only to sink the next day. Gwinn was riddled but avoided the torpedoes and limped off.

The American destroyers gained a bit of payback as they had blasted the Japanese destroyer Ayanami along with the secondary guns of the battleships. Ayanami succumbed around 2345.

SoDak's power was restored by 2336 and she began to head back toward Washington but then had to quickly turn away to dodge various burning and sinking destroyers. As she once again headed back toward the Japanese she was detected by Kimura's ships and then Kondo's.

South Dakota had again opened fire on Sendai which was astern of her. Her first salvo from her aft turret set the three scout planes on the fantail afire, Thirty seconds later, her second blew two of them overboard and alert damage-control people put out the fire on the third.

Every searchlight and gun the Japanese could bring to bear now targeted South Dakota. She soon found herself at the center of a hurricane of fire. She returned fire and her secondary batteries scored against the two Japanese heavy cruisers when Kirishima found the range - 5,000 yards. Fortunately, Kirishima's guns were pre-loaded with bombardment rounds with more in the shell hoists. Knowing it would require precious minutes to unload and reload with AP, Kirishima's captain chose to unload his main battery through the muzzles. South Dakota was hit some 27 times in just a few minutes with everything from 5” destroyer shells to the aforementioned 14-inch rounds. Her thick armor belt and turret armor saved her from critical damage, but her upper works were riddled with some 39 men killed and 60 wounded.

Lee had been watching all this on Washington's radar plot. In their zeal to hammer South Dakota Kimura and Kondo apparently forgot there was another American battleship out there.

Washington veered a bit to port to avoid the sinking destroyers, her crew tossing life rafts to the destroyermen bobbing in the water. Several voices implored the onrushing battleship, “G**dammit! Go get 'em!”

At the stroke of midnight the old Kentucky Rifleman had his clear shot at a range of 8500 yards. By 0007 it was over. Kirishima was a flaming and exploding wreck. Washington had fired 115 rounds. The Navy credited her with nine hits – pretty good shooting. However underwater investigations in the 1990s and research into Japanese archives indicate Kirishima was hit by up to TWENTY 16-inch rounds both above and below the waterline. She went dead in the water and sank at 0300.

Having now lost two battleships in three days, Kondo had had enough. He ordered his fleet to turn about and skeedaddle back to Rabaul. Washington shadowed them until it was clear they weren't coming back, then turned west to link up with Gwinn and South Dakota and escort them back to base.

Kondo ordered the four transports to beach themselves on Guadalcanal to hopefully land their men and supplies before the American planes could find them. They found them at dawn and blasted the transports into flaming wreckage.

The sinking of Kirishima marked the last major effort to reinforce the Japanese on Guadalcanal. During the first week of February, 1943, the Japanese destroyers did come down to Guadalcanal again, but this time to evacuate the 12,000 Japanese soldiers still alive on the island.

********

So, how did the Vols do against The Maxims?

1. The team that makes the fewest mistakes will win.

In total the Vols played a pretty good game. However, a number of mental errors and mistakes mitigated their efforts. The penalty bug reared its ugly head again with ten flags resulting in 85 yards. And it wasn't just the number or the yardage but the timing of some of these that really hurt. Then you have the dropped passes. Alongside the drop on fourth down, there were others throughout the game.

2. Play for and make the breaks. When one comes your way … SCORE!

One of Tennessee's best chances came at the end of the second quarter when Alontae Taylor forced a fumble killing a Gator drive. Tennessee drove down to the Florida 30 whereupon the usually reliable McGrath sliced his field goal attempt wide right. It was that kind of night.

3. If at first the game – or the breaks – go against you, don't let up … PUT ON MORE STEAM!

One got the feeling that past UT teams would have folded once the Gators took their opening possession down the field rather efficiently for a touch down. The 2021 version did not.

4. Protect our kickers, our quarterback, our lead and our ballgame.

Hooker was beat on all night. The Gators got him for five sacks and he rushed for 35 yards. That leaves out the hurries and hits he took after getting rid of the ball. Allowing Florida to march down the field to score after the Vols went up 14-10 was a direct violation.

5. Ball! Oskie! Cover, block, cut and slice, pursue and gang tackle … THIS IS THE WINNING EDGE.

You were warned. In these very pages reference has been made to the fact that Tennessee's blocking is sub-par. The offensive line is sort of a collection of walking wounded thrust into action because there is literally no one else. The defense played hard all night but, as Pat Ryan pointed out, by the middle of the third quarter they were done, Again, the 30 deserters presence would have made a huge difference but, to use a famous movie quote, that is spilt milk under the bridge.

6. Press the kicking game. Here is where the breaks are made.

Tennessee's special teams, upon whom praise has been heaped of late, seemed to say”challenge accepted!” They managed to accrue 30 yards in penalties and an ejection ON ONE PUNT. Then they followed that up with the errant field goal attempt at the end of the first half.

7. Carry the fight to Florida and keep it there for sixty minutes,

The team played hard right up to that last Gator possession where HeadLizard Mullen seemed determined to prove he is the orifice we've come to know. The Vol defense seemed to be saying, “You're kidding!” The simple fact was that Florida was more talented at virtually every position, certainly deeper at every position, and displayed that “X” factor that was discussed at the beginning. They simply KNEW they were going to win.

While it almost always a mistake to draw generalities from one contest, IF the Vols can stay focused, and IF enough of our tatterdemalion corps can stay healthy, we may yet see unexpected success this season with positive omens for future campaigns.

Suggested Reading

Jack Coggins, The Campaign for Guadalcanal

Paul S. Dull, Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy

James Hornfischer, Neptune's Inferno

Samuel Eliot Morison, The Struggle for Guadalcanal, History of U.S. Naval Operations in World War II, Vol V

USS Washington opens fire on Kirishima. (US Navy)